The Karez Well System | Uyghur Engineering Marvel

The karez (Chinese: 坎儿井; Uyghur: كارىز), located around the city of Turpan in China’s western region of Xinjiang, is an incredible example of an ancient irrigation system and the Uyghur ingenuity that developed it. The karez well system is considered the greatest Uyghur engineering accomplishment (nicknamed “The Underground Great Wall”) and even today is a marvel to visit and see.

The oasis town of Turpan would not exist were it not for the karez well system. Turpan is known as one of the hottest places on earth, with ground temperatures reaching a record 80° C (175° F). It’s almost certain that without the ingenuity of this ancient irrigation system, the Turpan would have disappeared centuries ago.

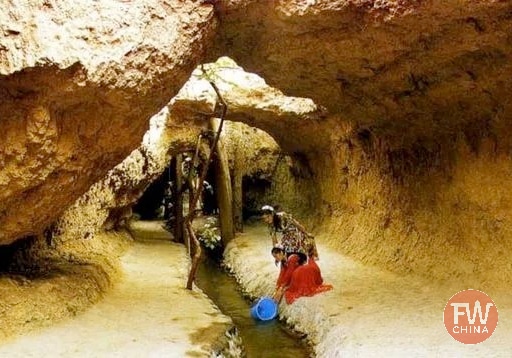

I’ve had the distinct privilege of studying and walking through many Uyghur karez tunnels over the past decade. It’s hard to appreciate just how amazing this feat of engineering is until you understand how it was done.

In my opinion, I believe the karez are more impressive than its above-ground brother – The Great Wall of China.

What exactly are the Uyghur karez? How were they built? And is it still possible to visit the karez well system today? Read through this excerpt from the FarWestChina Xinjiang Travel Guide to gain a greater appreciation for the Uyghur karez.

What are Uyghur Karez Wells?

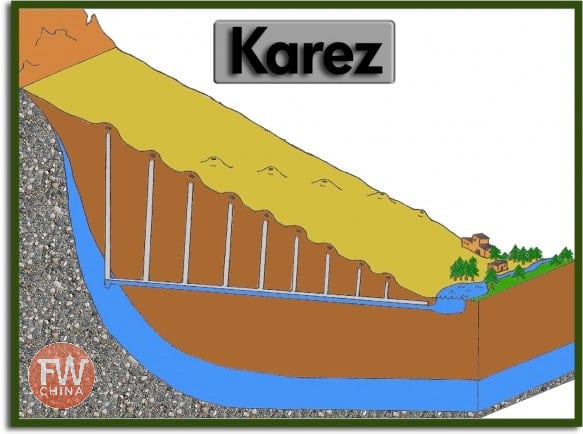

The Uyghur karez are a set of ancient wells built to connect an underground irrigation system that transported water from the Tianshan Mountains to the desert oasis of Turpan. They are very similar to the ancient qanat system developed by the Persian people of Iran in the 1st century BC.

The word “karez” simply means “well” in the Uyghur language.

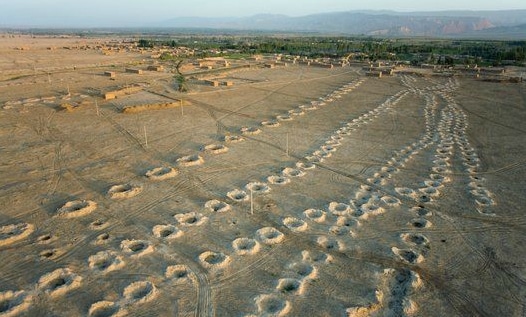

From above, the karez look like a series of ant hills criss-crossing the desert between Turpan and the mountains to the north.

If you were to take a cross section of this series of karez, you would see each of the wells linking the undergound canals that bring water to the fields of Turpan.

For those Uyghur living in the Turpan Depression, the second lowest point in the world behind the Dead Sea, it wasn’t just about getting water for irrigation. There was also the issue of that blazing heat.

You see, the reality of evaporation was problematic and made above-ground irrigation channels impractical. A new method had to be developed to transport mountain runoff to the flat land.

So the ancient Uyghur people found a way to bring the water through underground canals.

By digging at the shallowest part of the underground reservoir, fed by snow melt from the nearby Tianshan, the Uyghur engineers were able to harness the power of gravity to move the water toward the city. They constructed the underground channel using a series of shafts to dispose of the rock and ventilate the space.

These individual shafts usually average about 10-30 feet, but some go as far down as 100 feet.

How the Uyghur Karez Were Built

The karez are just a bunch of wells dug in the ground, right? Where’s the engineering genius in that?

It seems simple enough, but consider a few of the hurdles they had to face:

- How do you dig tens of thousands of these wells without the use of modern construction tools?

- How do you measure the slope of the underground canals so as to keep the water flowing?

- How do you move all the dirt from the canals out of the well?

- How do you make sure the canals don’t collapse on themselves?

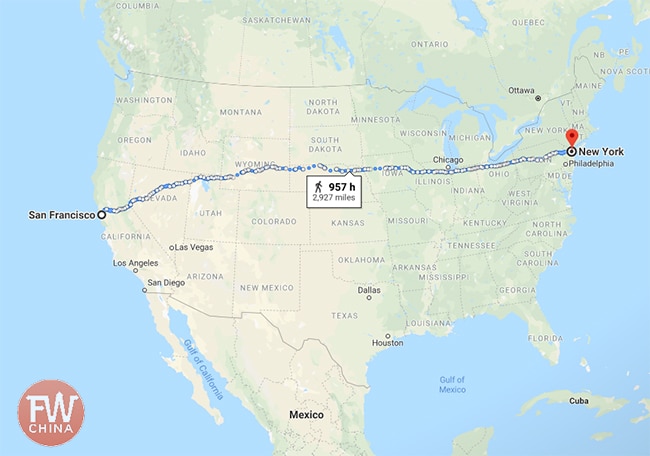

These are just a few of the engineering challenges the ancient Uyghur faced when digging out 5,000 km (3,100 mi) worth of underground canals.

And yes, you read that number right. The ancient Uyghur dug the equivalent of the distance between New York City and San Francisco, the entire length of the continental United States.

The first, and arguably most important challenge, was maintaining a slope (gradient) that would use gravity to keep the water flowing without forcing the engineers to dig too deep a well.

This was done using a primitive level tool similar to the one you see here.

Workers used this level to measure distance from ground level and to make sure that with each new well dug, they were reaching their goal of meeting the city of Turpan at the right level.

The actual digging was done by hand using a large work force of Uyghur labor. However, the method by which they entered the shafts and discarded of the dirt and rock was incredible at the time.

It was all done using a series of pulleys and rope tied to and ox or horse, similar to what you see here.

At this point, it was just a matter of time and labor required to build these karez. It’s nothing short of amazing when you walk through and see the results of all this work.

How to Visit the Karez in Turpan

While you’re in Turpan, it is possible to visit one of a couple different Uyghur Karez Museums west of the city. It is at these museums that you can get a brief history of the ancient karez well systems (similar to what I’ve already shared) as well as a chance to walk through one of the tunnels themselves.

The karez are one of a number of places I recommend visiting in Turpan. There are two primary tourist spots for the Uyghur karez in Turpan:

- Karez Well Amusement Park (坎儿进乐园 Kǎnerjìn Lèyuán )

- Karez Well Folk Custom Garden (坎儿进民俗园 Kǎnerjìn Mínsúyuán)

I tend to prefer the Folk Custom Garden, but honestly they both offer similar experiences. They both cost 40 RMB per person and can be visited in about an hour or so.

The karez museums are both located to the west of the city and are worth visiting while you’re coming back from your morning at Turpan’s Jiaohe ancient ruins.

A bit of a warning: These are not high-quality museums, so keep your expectations low. You will only be able to walk about 50 feet of actual karez and even that has been rebuilt for the purpose of tourism.

Also, most of the signs are all in Mandarin and Uyghur script, so knowledge of those languages is necessary to fully appreciate the museum experience (although having read this article will definitely help).

Since you’re already in Turpan, you’ll benefit greatly from the FarWestChina Xinjiang Travel Guide, the most comprehensive book on the Xinjiang region that is available. There’s an entire chapter dedicated to Turpan, including everything there is to do and see in and around the city.

You can buy the entire book on Amazon (thank you for your support!) or download the free planning chapter.

Final Thoughts | Uyghur Karez Wells

It is estimated that the ancient Uyghur people constructed over 1,100 karez wells connecting underground water canals spanning over 5,000 km (3,100 mi). As of 1949, only 600 karez were in use and thanks to modern advances in irrigation, only 300 karez are still active today.

These 300 wells only supply about 16% of Turpan’s water needed to grow the famous Turpan grapes.

The karez are certainly diminishing, but the government has made a concerted effort to maintain a few of them for the sake of history and study.

As a visitor, it’s worth taking an hour to walk through these Uyghur karez and transport yourself back to a time where water didn’t come out of a faucet.

No, this water came from snow melt hundreds of kilometers away, transported via the amazing canals known as the karez.

I went to the other place called Karez Paradise and I found it pretty good. It is still 40 RMB to get in, but they have a nice miniature of a Karez and people to give a presentation every 10 minutes or so. I’ve been to many other touristic sites all over China and you don’t get good explanations very often.

— Woods

[Reply]

Josh on February 29th, 2012 at 8:18 pm

Perfect! I’ve been looking for an alternative to the Karez Museum and it looks like you found one. If you have additional information (a pamphlet or something), please let me know: [email protected]

Thanks for your comment and I hope I can pass this information on to anybody else who is interested to travel out to Turpan.

[Reply]

It’s a remarkably good idea. Surprised not to have heard of it to date.

There are some tunnel complexes in Hebei that were dug as part of the anti-Japanese resistance in the 1940s that can still be visited today. In most cases they’ve heightened the tunnels and encased them in concrete for the convenience of the visitors, but it is still pretty impressive. I suspect that – as with these – there aren’t a lot of non-locals who visit the site.

[Reply]

Great blog post, a massive engineering feet for a society less educated, informed or technologically savvy than today. As I work in the mining sector, I’ve forwarded this blog onto my bosses, one of who was a geologist in Xinjiang a while back.

[Reply]

Josh on February 29th, 2012 at 8:20 pm

Thanks, James! Definitely interesting to ponder as you walk through the actual karez. Sometimes it’s hard to believe that it’s man-made and not a natural occurrence when you’re walking around.

[Reply]

Interesting post. Do you have a source on the 80 degree C thing? I think it might be a typo.

[Reply]

Josh on February 29th, 2012 at 8:10 pm

Thanks for your comment, James! I think I’m going to edit the article to reflect a good point you’ve made – that was the highest recorded *surface temperature*. The highest recorded temperature is about 40+ degrees Celsius.

The surface temperature is important here because of how evaporation in any above-ground solution for water transport would have been impossible. Thanks!

[Reply]

Your website is being a great source of information for Xinjiang. We visited today the museum and were quite disappointed. I wanted to point out though, that all explanations were in a very comprehensible English. Something is something.

[Reply]

Josh Summers on July 12th, 2017 at 8:21 pm

What exactly were you disappointed about?

[Reply]