Karamay Fire 1994 | The Real Story Behind China’s Worst Fire Disaster

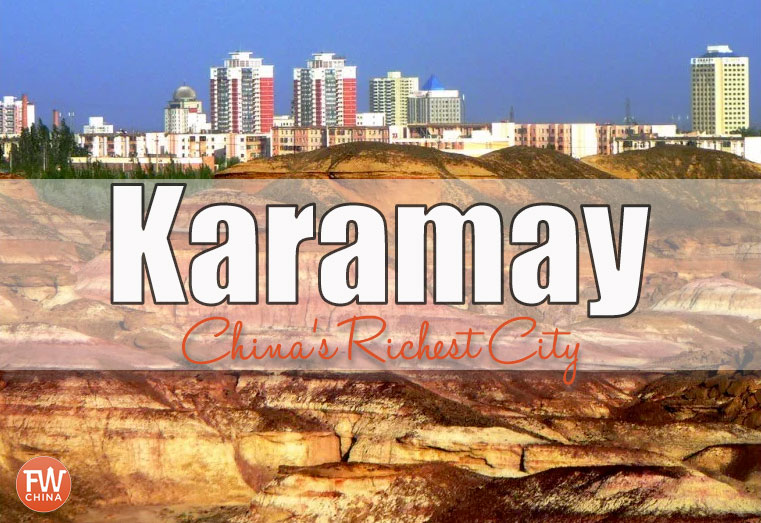

On December 8th, 1994, the small city of Karamay in China’s northwest Xinjiang province was home to one of the worst fire disasters in the country’s history. Dubbed the “Karamay Theater Fire” (克拉玛依大火), it’s notable not only for the unfortunate number of children that died (288) but also for the ensuing controversy and attempted coverup.

Everybody keep quiet. Don’t move. Let the leaders go first.

This short phrase, simple phrase still haunts the city of Karamay. As the years pass, it gets buried further and further back in everyone’s memory in hopes that one day it may actually be forgotten. But for now, the memory lingers.

During a cold winter day in 1994, a large fire broke out at the local Karamay theater killing 325 people, 288 of them school children.

It’s not a subject many people I’ve met here like to dwell on, obviously, but the 1994 Karamay Fire is well known as the one black mark that tarnishes the beautifully short history of this town.

History of the Karamay Fire

December 8th started out as a regular Thursday, as cold as most days are during a Karamay winter.

A simple performance was scheduled at the Karamay Friendship Theater that morning, a special bonus for those primary students who had proven themselves to be the best and the brightest in the city.

This event was so special, in fact, that many high-ranking city officials and Party members made an appearance. The theater was packed with leaders sitting up front and all the children seated behind.

The happy celebration ended in disaster, however, when a short-circuit in a light caught the backdrop scenery to catch fire, quickly engulfing the stage with flames.

The result of the fire was equally tragic and controversial.

Karamay Fire Controversy

Up to this point in the story, where scenery catches fire, everybody is in agreement.

From here forward, however, is where the controversy lies.

According to survivors, a woman who had either helped organize the performance or was a government official immediately stood up and told everybody to be quiet, sit still, and let the leaders go first.

Let the leaders go first.

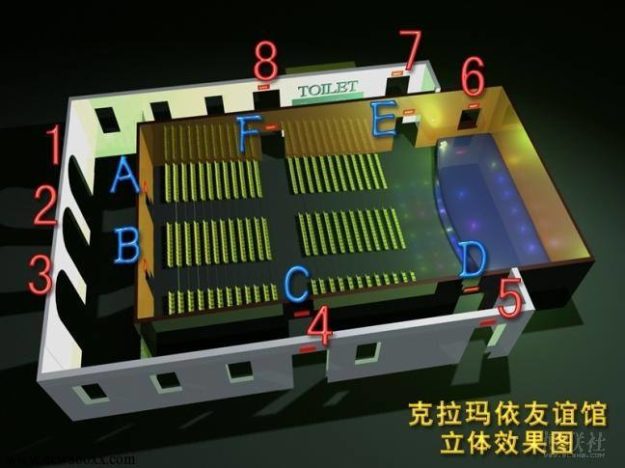

In retrospect, there were more than enough exits in the theater that would have allowed for everybody to evacuate safely. A total of eight (8) exits existed around the building. But there was a problem…

…only door 3 above was available for an escape. All others were either locked or blocked by steel fence doors that had dropped down during a short-circuit power failure.

Unfortunately, by the time the leaders had finished exiting the fire had spread out beyond control. For some unknown reason, the fire station was never alerted.

The lives of 288 children and 36 adults, mostly school teachers, were lost that day and it is a scar this city still bears in the faces of those survivors who were severely burned by the blaze.

Those that still live in Karamay (most moved) usually don’t walk around on the streets much to save their pride, but I have seen them occasionally.

The Aftermath of Xinjiang’s Deadliest Fire

The reaction to the Karamay Fire in 1994 was swift and fierce.

A government court quickly sentenced 14 people to prison, four of them high-ranking officials, for fleeing the scene and failing to call the fire station.

These details were never made public, of course, and the only noticeable change to the average Chinese citizen was a nationwide safety inspection issued days after the fire.

As for parents of the children who died, they were left with little recourse. They were never issued death certificates and no official tribute to the children was held. It was an emotional time for these parents that resulted in a number of informal protests both in Xinjiang and Beijing.

Most parents were offered compensation of up to US$8,000 but they were never issued a public apology.

Officials wanted to sweep this under the rug as quickly as possible.

A week after the fire, on December 17th, the local government announced that they were going to demolish the Friendship Theater entirely. The local Karamay residents, mostly parents, protested the move and surprisingly won out.

A compromise was reached.

The Friendship Theater remained shuttered but standing for three more years. Then, on September 24, 1997, the main theater was demolished, leaving only the front hall as a relic to remember the disaster.

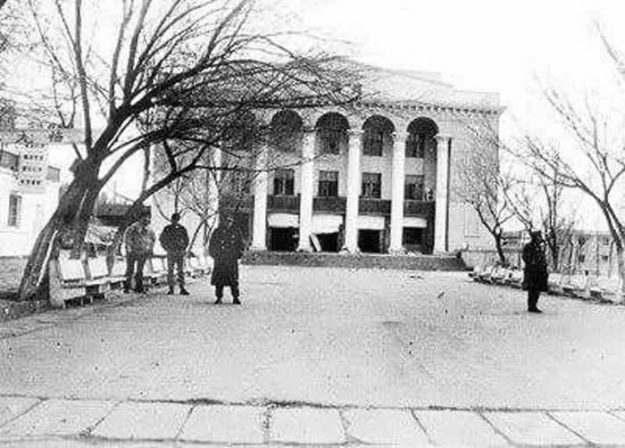

Today, the recognizable face of the theater still stands in the middle of a city park.

No plaque or mention of the first can be found on the building or in the park.

Reporting on the Karamay Fire

Not surprisingly, the details of this disaster weren’t widely known outside of Karamay until May of 2007. This is when a Chinese reporter for CCTV posted a documentary on his website with horrifying footage and family interviews.

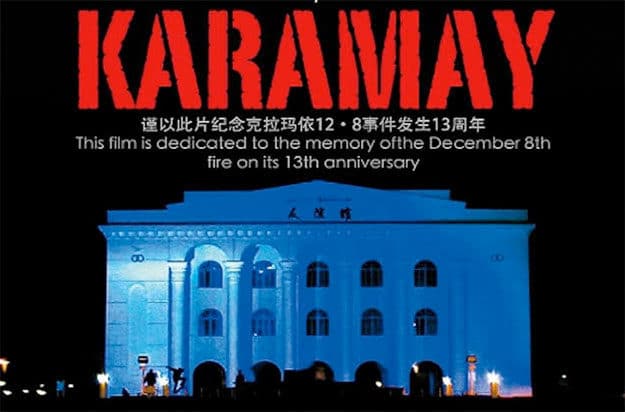

This 5-hour documentary film about the Karamay Fire by director 徐辛 (Xu Xin) was censored in China and banned from public broadcast.

International news organizations actually did run the story back in 1994, including an article in the New York Times, but the details there were sketchy and the focus of the article was primarily on the new safety inspections that had been ordered.

After the internet expose, international media again flocked to the story, the most detailed article being written in 2007 by Michael Sheridan of the UK Times (cached version).

Final Thoughts from a Former Karamay Resident

As a former resident of Karamay, I can see how it would be easy to forget something like this ever happened here.

There is no moment of silence each year on December 8th. There is no mention in the city newspapers. There is no memorial.

The only reminder of this incident is a white portion of the old theater that still stands on the edge of the People’s Square. You’d never know unless somebody told you, but this white-washed, unused building is actually the site of the darkest moment in this city’s history.

I wish to accomplish nothing by saying all this than to keep their memory alive. Not the controversy, but the memory of the 300 students and teachers who lost their lives in this city fourteen years ago.